Earth my body

Water my blood

Air my breath

And fire my spirit

(traditional chant)

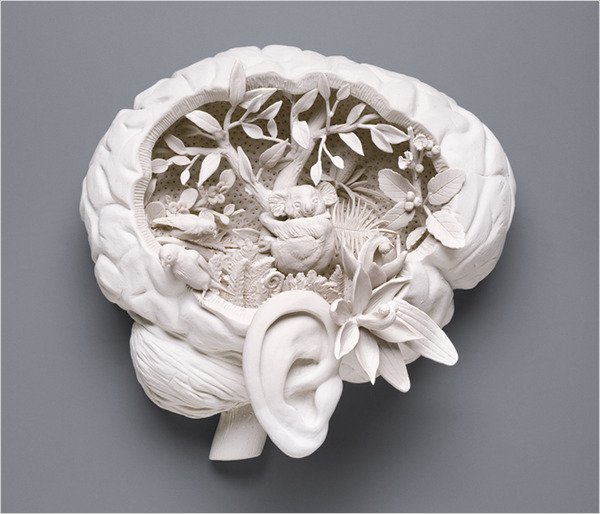

The bodymind work I explore and share is a yoga of contact, and of the connections and conversations that this puts in motion. Almost two decades now of increasingly quiet, careful, delicate attendance to my feeling-sense, to the inner chasms of my physical body as it cycles through the ebbs and flows of female embodiment, as well as to the edges of my body – the tender, ever-shifting meeting places between myself and the world as I stand, sit, or lie – all of these thousands of hours of tracking, listening, paying respectful attention, courting relationship, have taught me much that is of use in terms of how to live healthily. They have also gifted me a conviction that although the word “yoga” has come to mean many things (and that this is problematic in itself), I can best explain the yoga I practice as an opening of the channels of communication between the different parts of me, and between me and not-me. It foregrounds communication and the spontaneous arising of community – between my breath and my spine, between my feet and the grass, between my skin and the winged creatures that zip past on these warm, wet summer days, with the clay that lies under the lawn in this part of the country; as much as the community that is my family, my neighbours, my group of friends, my students and my colleagues.

My formal practice takes place in a wild and overgrown corner of English countryside. These days, I am, I notice, twitchy and irritated by the straight lines, perfect cleanliness and shiny pseudo-zen vibes of studios and purpose-built centres. They served me once … But mine is a yoga of hedgerows and woodlands; meadows, lakes, and rivers; puddles, brief, dazzling heat and light, interminable rain and infinitely nuanced shades of grey-brown. The land that I live on, the country of my birth and the customs and habits of its denizens (both human and more-than-human) have nurtured and expanded, pruned and refined my experience and understanding of embodiment, as they have for us all, anywhere else you can think of. Though yoga may be claimed a technology of transcendence, an individual’s practice will always reflect the physical, social, cultural and religious environment in which it takes place. Accordingly, our practice also impacts upon these systems – in our tiny way, we contribute to the cultures of which we are part.

My connection with myself is rooted in the land that I blessed to have as a support in this challenging work, and in local and specific ways of knowing. I am a householder who is required to chop wood on a daily basis to ensure warmth and comfort for my family for more than half of the year; I walk many miles through the countryside each week to facilitate my children’s busy lives. I am unromantic about nature, being at its mercy in my old, tumbledown house, but I am nonetheless grateful that my body has direct experience of its wildness, fierceness, and harshness, as well as its bounties and beauties and blessings, and that I am in deep relationship with the land here. I know it to be a rare privilege to be as intimate with areas of woodland and fields as with a lover’s body.

My formal practice takes place outdoors if at all possible. In this secluded, tangled garden, leading to a gnarled apple orchard, I can stretch and rest, extend and contract my body and breath, delighting in syncing my internal human rhythms with the unfolding and the retraction of the seasons. I can lie with the wind caressing my skin, breathe the rich soil, reach sunwards, fall and nestle into the roots of the trees. I wrap in many jumpers, and have been known to take hot water bottles in order to savour the coming spring in the sharp, still-winter-really air, or to eke the last of the precious golden light of autumn before the long darkness of winter. I practice in gentle summer rain, brief thunderstorms, unpredictable gusts of wind, and fierce heat. Nature is not a place to visit on a sunny Sunday afternoon, or a concept I read about. It is not a pretty backdrop to photos of me in advanced asana, or a convenient symbol upon which to explain yogic concepts to students. it is part and parcel of my embodiment, my understanding of that, and even my ability to articulate that. It is literally the ground from which it all springs – and, in a surprising and graceful turn of events, the ground to which it returns, now that I teach in a little wooden barn a minute’s walk from my house.

Although I have had skilled and experienced teachers in relatively traditional (if highly Westernised) yoga, applied yoga and yoga therapeutics, I take more inspiration from North European wisdom traditions than from Indian philosophy. These traditions are my heritage, and they are rooted in people’s connection with this land. They speak of and to my lived experience. My formal teaching has been in “yoga”, but this found fertile ground in time I had previously spent at festivals, raves and outdoor parties, and in my private forays into sacred sexuality, paganism and goddess worship. My apprenticeship has been in balancing committed practice with the informal but highly challenging discipline of being a wife and parent, at least as much as a “yoga teacher”. So while I am no fan of the yoga mashups mushrooming in the “anything goes” culture of the free market (rage yoga? snoga? hip hop yoga? yes, they’re all things, apparently), I must own that I respond more readily and wholeheartedly to what I know of native shamanism, paganism, and modern-day revivals such as wicca and the Goddess movement, than I am by what I know of yoga philosophy.

I understand that for many scholars and practitioners, this might be highly problematic. For one thing, my knowledge of the philosophies and worldview that shape yoga philosophy is minimal, and whether this qualifies me as a “yoga teacher” can certainly be called into question. I practice asanas, pranayama, pratyahara, the yamas and niyamas, and make forays into dharana and dhyana, in a country far removed geographically and culturally from the land that these practices are rooted in, and I splice them with nuggets of wisdom, and occasionally other practices, that I have received (and tested) from very different cultures. The practices intersect with my uniquely-conditioned bodymind, and produce a unique expression. It is undeniably a removal – even a severing – of yoga from its roots.

Perhaps no practice is ever “pure” or transcendent in the sense that it exists outside of the human experience, which is by its nature conditioned, and therefore both variable and limited. Certainly, I contend that a yoga pose – let’s say trikonasana – does not exist as such by itself. It needs a human bodymind to enact it. Despite the flattening effect of social media, in which a seemingly endless parade of “perfect” poses are displayed in desirable locations (each replete with their comment streams proclaiming “inspirational” and “beautiful” and the breathless “wow!”), yoga is participatory, and therefore unique to each practitioner. Thousands of books, websites, and blogs exist which describe in minute detail the external rotation of the front leg in trikonasana, the alignment and the feeling tone and the breathwave in the chest, but trikonasana does not exist for you until there you are, stretching your limbs and your lungs, easing and opening into the unfolding of the moment.

I freely own that the dilution of yoga that I enact and disseminate through my teaching might allow for all kinds of misunderstandings, and resultant misrepresentations of this thing called yoga. This dismemberment plays a large part in the undeniable watering-down of the teachings that is recognised and railed against by so many now (even if it’s to contrast their own “deeper” understandings and teachings). Perhaps it becomes part of another narrative – that of the uneasy coexistence, a subtler, modern form of the dominator/dominated paradigm, that has existed between Britain and India since Britain consolidated its trading presence there, and used that as leverage to control the whole country by the end of the 18th century. (This article says that 29 million Indian people lost their lives under the Raj; this may be a conservative estimate according to others.)

Recent scholarship is showing that yoga has always been syncretic, and that although some key features tend to remain wherever and whenever it flourishes, it is infinitely adaptable. The techniques and practices of yoga are rooted in the specific culture of its birth, where it flourished, and for the inheritors of whom many wise and thoughtful people (and some zealots) are working to reclaim and reframe it within the wisdom traditions of that part of the world. But “my” yoga is an indigenous practice, and in truth it cannot ever be otherwise. To pretend so would be a dishonesty, an overreach, an arrogance; and a continuation of the colonising mindset. I have read and studied Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, but I cannot teach “Patanjali yoga” with the kind of teachings I have myself received, from the teachers with whom I have studied, and with the kind of life that I live. I have read some tantras, but I cannot truthfully teach tantrik yoga, never having had a tantra teacher.

From my personal vantage point, I observe that this is a chronically unlooked-at facet of many Western yoga teachers’ practice and teaching. I suppose that if a spiritual technology is alleged to be transcendent in that it speaks to and of all human experience, this could lead to a conviction that one’s practice (from which so many teachers’ actual teachings spring) – such an intensely personal experience – is done some kind of disservice through looking at it through lenses of history and politics. I think I can understand this mindset. However, it can intersect with an unacknowledged sense of entitlement in a very uncomfortable way. For instance, what are we to make of teachers who, never having studied with an Indian teacher themselves, travel with their own privileged and wealthy students to Indian retreat centres owned by Westerners, proclaiming that “we’re all one” while Indian people, the rightful inheritors of yoga, clean their toilets for a few rupees a day?

The demands and delights of a householder’s life mean that I am unlikely to personally run an exotic retreat any time soon, but this issue is a huge dissonance for me. Yet, it is not one that I want to comfortably and conveniently resolve. I consider that I have a responsibility to hold the following questions in mind:

Is my practice yoga? Can I claim it as such?

Can I call what I teach yoga? Who gains from this, and at what cost; and who loses? Is my personal gain inseparable from these losses?

I have been to India precisely once. I lay on a beach, visited waterfalls, felt that peculiar combination of being both an alien and at home (like a good festival, it is leaving India, as my husband pointed out, that causes the culture shock, not the country itself). And I did a shitload of yoga practice. Yes, it was beautiful, deep and profound. But the country of my birth is also a land of great beauty – a land of wild roses and green hills; mists and bubbling rivers; kingfishers and dragonflies and buzzards. Britain is, of course, a ravaged land, a raped land, a terrain with too few guardians. Our ancient woodland cover has declined greatly. Only 3,090 square kilometres of ancient woodland survive – less than 20% of the total wooded area. More than eight out of ten ancient woodland sites in England and Wales are less than 200,000 square metres in area, only 501 exceed 1 square kilometre, and a mere fourteen are larger than 3 square kilometres. So many of our indigenous birds, plants, fish and insects are under constant threat, and their populations in severe and steep descent, that it is hard to even get up to-date-figures, but a recent report concludes that 10% of the UK’s species are currently threatened with extinction. Ash dieback is the latest disease to rip though what is left of our woods. Large-scale fracking continues to be an ever-present menace.

Britain is ancient. In May 2013, footprints that are at least 840 000, and possibly as old as 950 000 years, were discovered on a beach in the village of Happisburgh in Norfolk, on the east coast. (They were found in a newly-uncovered layer of sediment, and were destroyed by the tide within two weeks of exposure.) Three years earlier, archaeologists had discovered flint tools near the site, which were dated to 800 000 years old at the youngest, and are possibly as old as 970 000 years. The Happisburgh prints are the oldest ever uncovered apart from those found in eastern Africa, which are estimated at around 4 000 000 years old. Archaeology has also shown that Britain has been continuously inhabited for at least 13 000 years. If we can set aside our conditioning and narrow education about civilisation and the march of progress, this agedness, and continuity of life, surely suggests that the indigenous population of this land would have had their own wisdom traditions. Perhaps they rivalled technologies such as yoga in their sophistication. We may continue to be fascinated by the combination of antiquity and exoticism of the highly-developed cultures of the Indus Valley (perhaps 8 000 years old), by cities such as Catal Huyuk in modern-day Turkey (9 000 years old), but it is troubling to me that we know so little of our own history and heritage, and that our education does not generally permit us to join the dots between the history of this land and our current lived experience. And perhaps our fascination with the exotic, and our wholesale buying-into systems of knowledge such as yoga, serves to further obscure our own cultural and spiritual birthright.

It is imperative that we do not use our privileged positions as the inheritors (and therefore wielders) of enormous relative cultural power and wealth to minimise the very real loss that people suffer when their traditions are stolen – and then sold back to them at a price. Debates rage on the interwebs about cultural appropriation (see here, here and here for an introduction to this complex topic). Too often in this disembodied form of communication, participants lose sight of the real opportunity for mutual understanding; some retreat in angry indignation that that their personal losses, their personal feelings of deep powerlessness within the larger systems that govern our lives, are unacknowledged. Those who fall into or who take on the role of agitators or educators can seem to lose sight of our common humanity, and forget that the teasing out of our shadowy heritage is painful work which is accompanied by strong emotional reactions. But in considering issues of cultural appropriation, it feels relevant to me to acknowledge the spiritual losses of the appropriators as a driver of their behaviour.

Questions of appropriation are currently being discussed with fervour in America, where citizens are still conditioned to some extent by narratives of the American Dream. The Declaration of Independence proclaims that all are equal, with the right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”. Founded on a set of ideals around freedom (democracy, rights, liberty, opportunity, and equality), the American Dream takes the form of opportunity for prosperity, wealth and material accumulation, equally and always available to all citizens. An upward curve of success, achieved through hard work in a society with few barriers, is part of the prevailing mythos. Writer and historian James Truslow Adams opined in 1931 that ”life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement” regardless of social class or circumstances of birth.

These high ideals, however, are undercut by the bare facts of the genocide, land theft and spiritual warfare that the founders of the States visited upon the indigenous peoples of the land itself. Migration of Europeans began in the 15th century, and political tensions, ethnic violence and social disruption were the predictable results of the yawning chasm between the world views of the invaders and the native peoples. Smallpox alone, brought by settlers and to which native dwellers had no immunity, is thought to have accounted for the loss of some eighteen million lives. (There are verified stories of deliberate infection.) Mass starvation resulting from land theft and calculated disruption of traditional ways of life killed countless others. As I write, construction crews are destroying sacred sites and poisoning drinking water in North Dakota, the home of the Sioux tribe, in order to build the $3.7bn pipeline that is required to transport fracked oil. (Protestors representing many, several traditionally mutually hostile tribes, say that the pipeline is the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy in which a zuzeca – black snake – threatens the world.)

England has a similar history of bloody warfare against its ancient inhabitants. The Roman invasion that began in 43CE decimated the population of Britain, sublimated its survivors, and systematically destroyed the cultural and spiritual heritage of the survivors. Historians also surmise that something dramatic happened in England just as the Roman empire was collapsing. A second wave of obliteration in the 4th century CE, by the Anglo-Saxons, reduced the Romano-Celtic population (estimated at between 2 million and 3.7 million people) by about a million.

The study of religious and spiritual practice in the early Anglo-Saxon period is difficult, because most of the texts that may contain relevant information are not contemporary, but written later by Christian writers who tended to have a hostile attitude to pre-Christian beliefs, and who are likely to have distorted their portrayal of them. And so of course, these brief histories of England and the USA are fragmented and decontextualised. They are also regularly subject to hijacking by political agendas, either to ally indigenous peoples with troubling notions of primitivism (which the western world views as “backward” and from which people need emancipation via Western aid or ideologies), or to claim intellectual territory (the charming Nick Griffin of the far-right BNP refers to British “aborigines” in order to draw attention to those who live in Britain but are immigrants or refugees). I tell them here to illustrate that citizens of the two countries – and we could include many others here, too – have had significant parts of their histories effectively erased. I have only become aware of them recently, although I remember having inklings of erased stories, of counter-narratives, and of how stories and histories are owned, when at school.

These histories are highly relevant to modern-day practitioners of yoga, because opening ourselves to them forces us to confront questions of whether we practice in a vacuum, or within the context of social responsibility and care (that oft-used yoga term, “community”). It also requires that we face the loss of our spiritual heritage and what that might mean.

I have been wondering how British and North American yoga practitioners make sense of the complex and difficult emotions these histories might give rise to. Researchers in the complementary fields of neuroscience, psychiatry, and interpersonal biology know that unresolved trauma impacts upon a person’s sense of self at every level, including the physical. Further, work with surviving members of oppressed and or marginalised communities, such as Australian Aborigines, Canadian First Nations peoples and holocaust survivors, is showing that trauma (particularly if deliberately inflicted) has a measurable trickle-down affect upon subsequent generations.

What might this mean for those of us drawn towards a contemplative life, in which a practice such as yoga might play a pivotal part? What memories of violence, hatred, terror might be inadvertently woken from the depths of a psyche by a practice? How far back in our personal family histories do we need to travel in order to directly encounter events that give rise to fear, loss, grief? On a community level, how do we make sense of the guilt and shame, and the tendency to blame and shift responsibility for events that caused immeasurable loss to others? How do we experience these ghosts of emotion in our own bodies? What pit of psychological horror might we unwittingly fall into in following the most innocuous of instructions in a yoga class, such as “stand with your feet on the ground”? What if that ground ran with blood, and our direct ancestors were implicated?

It seems to me that indigenous spirituality and religion; ways of knowing, of understanding ourselves and of the world, have been lost or almost completely obscured. Certainly, lineages do exist, but they tend to stretch back no further than a couple of hundred years, to be a hodgepodge mix of occultism and the alluringly exotic, or to be so hidden to even a determined seeker that they are, to all intents and purposes, invisible. As with yoga, this is not to claim that wisdom traditions can ever be pure or unadulterated, or that their value lies mainly in their age or alleged untaintedness; but it is to recognise that for most people here in the UK, authentic spiritual heritage is absent.

But: is there not a strange and circular irony in utilising psycho-spiritual tools from a different culture, country and historical period, in order to integrate and make peace with the uncomfortable emotions we experience as the inheritors of ruthless, deliberate violence against people from that very timespace?

Might there be some relationship between the “it’s all good”, “follow your bliss” model of yoga that currently holds sway, and our blindness to the histories of the peoples of these lands? Could this paradigm (/parody) of yoga be part of a process of continuing our ignorance; even, our determined unconsciousness?

What are the mechanisms by which we personally escape discomfort? Is yoga one of them? Is this elision of parts of our humanity – our vulnerability, our sensitivity, our tendernesses and capacity for empathy with others – a violence against ourselves? Is this intrusion into our private emotional landscape by notions of what we think we should and should not feel a kind of colonisation of our psychological space? Does this become part of the larger ongoing process of colonisation of land, property and cultural artefact?

I have no wish to minimise or belittle the sophistication and depth of the yoga tradition. But I feel strongly that whilst an experienced teacher to whom I was able to commit as a student would be able to teach me much that I cannot even conceive of, I am qualified to speak from the vantage point of my experience. And from here I want to assert two things. Firstly, that it’s my observation that while the yoga tradition has codified, refined and developed techniques of knowledge, the arising of the desire for this in the first place is a spontaneous phenomenon that occurs in all cultures and societies, from antiquity to the present day. The form will and indeed should vary according to the environment, or it risks essentialism and ossification. My responsibility is therefore to be as clear and honest about my positionality as regards what I do in relation to what I know of yoga’s heritage, and to remain committed to dialogue. Within this, however, I want to be able to walk the tightrope that is strung between adherence to traditional yoga, and creating an individual, freeform mashup that might represent my own interests but bears little relationship to the traditions it references. I’m pondering whether this approach might in itself be an act of yoga.

Secondly, we are in the midst of an ecological crisis, the like of which the world has never known, and the true horrors of which we are largely unaware. The world in which yoga is now practiced and taught is very different to ancient India, and yoga has to be responsive to the demands of both its students and of the world that they inhabit. I see no use any longer in insisting on the sameness and the unchangeability of the human psyche if that does not allow me to engage with this inescapable fact: that ancient Indian yoga masters can have had no comprehension of our chronic stress, deadened and hyperstimulated senses, almost total lack of attunement to the natural world including our own bodily wisdom that is now so common as to be “normal”, and the ecological precipice on which we tip. So as Toby Hindson says, “the Earth speaks and we have to act”. Can a yoga practice be earth-centric? If we utilise practical, tried-and-tested techniques of self-knowledge in the service of garnering knowledge of our embodied connection to the land we practice on (and with), might that not now be a more noble aim than Patanjali’s yogas-citta-vrtti-nirodhah – ‘Yoga is the restriction of the fluctuations of consciousness’? (translation by Georg Feuerstein)

And so … I have to come back to my own body, this life, living on this piece of land. I have spent so many frustrated years as a practitioner and teacher, waiting for my children to get older and more independent, my financial situation to improve, my practice to somehow mature, so that I can search out a true teacher, spend an extended period of time focused on formal practice, travel to India to look for yoga’s authentic roots. I realise now that not only is the drive to do these things unlikely to be resolved by chasing after them, but that I am perpetuating both an idea of yoga that does not serve me, it, or this precious planet.

So. This land. I want to trust that those who share it with me – the basket-makers, gardeners, doulas, herbalists, walkers; the poets and musicians and storytellers – those rooted in pragmatic, embodied traditions and lineages, might be the heirs to our wisdom traditions. This body. This breath. These feet, contacting these blades of grass, part of a patch that, along with elder and nettle and herb robert, grows up the trunk of this tree. The physicality of this land; standing and lying and sitting upon it not as an abstract concept of body and gravity, but as a felt relationship. This wood. This life. I have to trust that it is enough.

this is about so much more than yoga eh. You are a very knowledgable and articulate being…feel proud at finding such a strong voice, my love

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this so much. Love the consciousness that gave rise to it.

Thank you for being you. And for writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing this article of your thoughts!

As another British “yogi” I can empathise with many of the issues you put forward & I too have struggled with many of these same (or almost identical) issues in my practice. How authentic can my teaching of yoga really be if I have never been to India, or even had an Indian yoga teacher myself?

Personally I resolve (or keep at bay until the next round of exploration) this by realising that what I teach is needed by my students. To them it does not matter whether I am steeped in “real” yoga; what matters is how they feel during their practice & the peace they take away from it.

I recently read a memorial of a renowned Indian yogi by one of their students. They remembered asking a similar question of their Guru: “What I teach is so different to what is taught in India, so how can I call what I teach “yoga”? How can I tell my students what I teach is authentic, when I feel a fraud?” The response was that it does not matter – the fact that you are bringing your version of yoga to a wider audience, along with all of the benefits, is the important thing: those who are called to explore their practice more deeply will find the teacher they need.

The whole concept of “yoga” is itself ephemeral – yes there are ancient writings that appear to describe what we now call yoga, but the people who wrote them lived in a totally different world to us! Does it matter whether they would recognise what we teach as “yoga”? Is it not natural for a concept to evolve through time, being added to by its practitioners & enriched by its followers?

I believe that this is an important discussion to have…

LikeLiked by 1 person